Home » Posts tagged 'emotion'

Tag Archives: emotion

“Social spacing”, not “social distancing”: Deepening connections while staying safe

As the SARS-CoV-2 virus spreads across the globe to create the COVID-19 pandemic, people have been requested to stay out of public spaces and reduce interpersonal contact to reduce the transmission of the virus. This process has the unfortunate name of “social distancing“, which has connotations of removing one’s self socially and emotionally as well as physically from the public sphere. Before modern communication technologies existed, those might have been unfortunate side effects of such a containment strategy. However, with all the methods available to us to stay connected across large gaps between us, I propose we call this effort:

Social spacing.

In this way, we emphasize that it’s the physical space between people we seek to minimize, not the interpersonal bonds we share. “Social spacing” entails a simple geographic remove from other people. It also invites people to become creative in using technological means to bridge the space between us.

How to stay faraway, so close

When using technology to stay connected, prioritize keeping deeper, meaningful connections with people. Use Skype or other video messaging to see as well as hear from people important to you. Talk to people on the phone to maintain a vocal connection. Use your favorite social media site’s individual messenger to keep a dialog going with someone. Have individual or group texts for select audiences of messages.

In these deep, close, personalized connections, it’s OK to share your anxieties and fears. Validating that other people are concerned or even scared can help them feel like they are grounded in reality. However, beyond simple validation, use these deep connections to plan out what to do, to take concrete actions to live the lives you want. To the extent possible, share hobbies or other pursuits together if you’re shut off from work or other personal strivings for success.

- Move book clubs from living rooms or coffee shops to speaker phone calls or group Zoom sessions.

- Find online or app versions of bridge, board games, roleplaying adventures, or other fun things you might do together in person – or find new things to do online.

- Set an appointment with some friends to watch a show or movie on TV or streaming media. You can then have a group chat afterward to share your reactions. Then again, maybe you all would enjoy keeping the line open as you’re watching to comment along in real time!

- Curate playlists on Spotify or other music sites to share with your friends to express your current mood or provide some uplift to each other.

- Make a creative group so that you write novels, paint pictures, or pursue other artistic endeavors together.

- Broaden your palate and share culinary adventures with your friends with social cooking sites or online cooking classes. Share your favorites with your friends, or have conversations as you cook to help debug recipes.

- Exercise your body and share online workout videos or apps with your friends. Setting up a friendly competition might even prolong your activity gains after the pandemic passes.

- Learn skills through shared courseware from Khan Academy, LinkedIn Learning, or other sources.

These kinds of personalized connections can be prioritized over broad social media posts. In that way, you have more of an influence over your audience – and you can ask for a deeper kind of support than a feed or timeline might provide. If you use social media, use language laden with nouns and verbs to minimize emotional contagion. Share information from trusted, reputable sources as close to the relevant data as possible. I recommend the University of Minnesota’s COVID-19 CIDRAP site for a transnational perspective.

When too many connections and too frequent news become too much

You might find that the firehose of information overwhelms you at times. If you find yourself getting more anxious when you watch the news or browse social media, that’s a good sign that you’d benefit from a break. As a first step, you might disable notifications on your phone from news or social media apps so that you can control when you search for information rather than having it pushed to you. Other possibilities include:

- Employing the muting options on Twitter, snooze posts or posters on Facebook, or filter words on Instagram.

- Using a timer, an app, or a browser extension to limit the time you can spend on specific social media sites.

- Turning off all your devices for a few hours to really unplug for a while.

Through these methods, you can give yourself space to recharge and stay connected even as you’re socially spaced.

The (mis)measure of emotion through psychophysiology

On New Year’s Eve 2016, Mariah Carey had a…notable performance in which she had difficulties rendering the songs “Emotions” and “We Belong Together”. She roared back on New Year’s Eve 2017, sparking the first meme of 2018.

On New Year’s Eve 2016, Mariah Carey had a…notable performance in which she had difficulties rendering the songs “Emotions” and “We Belong Together”. She roared back on New Year’s Eve 2017, sparking the first meme of 2018.

Alas, it is unlikely that the field of psychophysiology will un-mangle its measurement of emotions with reflexes in such a short span of time.

My lab uses two reflexes to assess the experience of emotion, both of which can be elicited through short, loud noise probes. The startle blink reflex is measured underneath the eye, and it measures a defensive negative emotional state. The postauricular reflex is a tiny reflex behind the ear that measures a variety of positive emotional states. Unfortunately, neither reflex assesses emotion reliably.

When I say “reliably”, I mean an old-school meaning of reliability that addresses what percentage of variability in a measurement’s score is due to the construct it’s supposed to measure. The higher that percentage, the more reliable the measurement. In the case of these reflexes, in the best-case scenarios, about half of the variability in scores is due to the emotion they’re supposed to assess.

That’s pretty bad.

For comparison, the reliability of many personality traits is at least 80%, especially from modern scales with good attention to the internal consistency of what’s being measured. The reliability of height measurements is almost 95%.

Why is reflexive emotion’s reliability so bad?

Part of it likely stems from the fact that (at least in my lab), we measure emotion as a difference of reactivity during a specific emotion versus during neutral. For the postauricular reflex, we take the reflex magnitude during pleasant pictures and subtract from that the reflex magnitude during neutral pictures. For the startle blink, we take the reflex magnitude during aversive pictures and subtract from that the reflex magnitude during neutral pictures. Differences can have lower reliabilities than single measurements because the unreliability in both emotion and neutral measures compound when making the difference scores.

However, it’s even worse when we use reflex magnitudes just during pleasant or aversive pictures. In fact, it’s so bad that I’ve found both reflexes have negative reliabilities when measured just as the average magnitude during either pleasant or aversive pictures! That’s a recipe for a terrible, awful, no good, very bad day in the lab. That’s why I don’t look at reflexes during single emotions by themselves as good measures of emotion.

Now, some of these difficulties look like can be alleviated if you look at raw reflex magnitude during each emotion. If you do that, it looks like we could get reliabilities of 98% or more! So why don’t I do this?

Because from person to person, reflex magnitudes during any stimulus can differ over 100 times, which means that it’s a person’s overall reflex magnitude that raw reflex magnitudes are measuring – irrespective of any emotional state the person’s in at that moment.

Let’s take the example of height again. Let’s also suppose that feeling sad makes people’s shoulder’s stoop and head droop, so they should be shorter (that is, have a lower height measurement) whenever they’re feeling sad. I have people stand up while watching a neutral movie and a sad movie, and I measure their height four times during each movie to get a sense of how reliable the measurement of height is.

If all I do is measure the reliability of people’s mean height across the four sadness measurements, I’m likely to get a really high value. But what have I really measured there? Well, it’s just basically how tall people are – it doesn’t have anything to do with the effect of sadness on their height! To understand how sadness specifically affects people’s heights, I’d have to subtract their measured height in the neutral condition from that in the sad condition: a difference score.

Furthermore, if I wanted to take out entirely the variability associated with people’s heights from the effects of sadness I’m measuring (perhaps because I’m measuring participants whose heights vary from 1 inch to 100 inches), I can use a process called “within-subject z scoring”, which is what I use in my work. It doesn’t seem like the overall reflex magnitude people have predicts many interesting psychological states, so I feel confident in this procedure. Though my measurements aren’t great, at least they measure what I want to some degree.

What could I do to make reflexive measures of emotion better? Well, I’ve used four noise probes in each of four different picture contents to cover a broad range of positive emotions. One thing I could do is target a specific emotion within the positive or negative emotional domain and probe it sixteen times. Though it would reduce the generalizability of my findings, it would substantially improve reliability of the reflexes, as reliabilities tend to increase the more trials you include (because random variations have more opportunities to get cancelled out through averaging). For the postauricular reflex, I could also present lots of noise clicks instead of probes to increase the number of reflexes elicited during each picture. Unfortunately, click-elicited and probe-elicited reflexes only share about 16% of their variability, so it may be difficult to argue they’re measuring the same thing. That paper also shows you can’t do that for startle b links, so that’s a dead end method for that reflex.

links, so that’s a dead end method for that reflex.

In short, there’s a lot of work to do before the psychophysiology of reflexive emotion can relax with its cup of tea after redeeming itself with a reliable, well-received performance (in the lab).

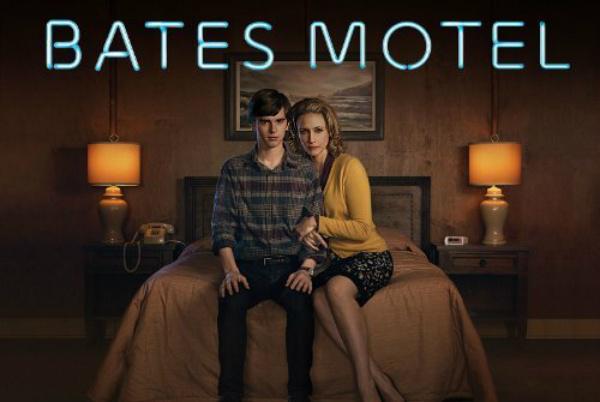

Hannibal, Bates Motel, and trait absorption

In 2013, two remarkable TV shows hit the air- and cable-waves that provide backstories of two of cinema’s most notable villains. Hannibal features a retelling of the story of Hannibal Lecter and Will Graham that surprises even the most die-hard connoisseurs of Thomas Harris’s original novels and the movies that have been made from them. Bates Motel fills in the history of Norman Bates, tracing his descent from a gawky teenager into the Psycho murderer.

In 2013, two remarkable TV shows hit the air- and cable-waves that provide backstories of two of cinema’s most notable villains. Hannibal features a retelling of the story of Hannibal Lecter and Will Graham that surprises even the most die-hard connoisseurs of Thomas Harris’s original novels and the movies that have been made from them. Bates Motel fills in the history of Norman Bates, tracing his descent from a gawky teenager into the Psycho murderer.

The personality trait of absorption is strongly evident in a character in each series. Absorption is a strange trait in the Giant 3 model of personality that doesn’t fit cleanly anywhere. It was originally designed as a measure of hypnotic susceptibility, but it’s been refined over the decades to emphasize getting lost in one’s own experiences, whether those experiences be enthralling external stimuli or deeply engaging thoughts and images that come to a person’s mind. Absorption relates equally to the superfactors of Positive Emotionality and Negative Emotionality, indicating that it predisposes people to strong emotional experiences. Within the Big Five model of personality, it’s associated with the fantasy proneness and emotionality facets of Openness to Experience, not the parts of Openness that are associated with playing with ideas or political liberalism.

Some of my recent work has examined how absorption is related to initial attention to emotional pictures and subsequent attention to noise probes. We found that people high in absorption had more emotional attention to emotional pictures (both pleasant and aversive) compared to neutral pictures. Thus, people high in absorption get wrapped up in what they’re seeing when it’s emotionally evocative. Furthermore, we found that people high in absorption show less attention to a loud noise probe during all pictures. It’s as if they’re so wrapped up in processing the pictures that they don’t have as strong an ability to disengage attention to process something else coming in a different channel (that is, hearing as opposed to sight).

How does this apply to our two fictional characters? Both of them get really absorbed in the imaginal part of their internal experience, which wreaks havoc on their emotional lives. Will Graham’s unique perceptual gifts entail mentally reconstructing a crime from the residues left at the crime scene. He may be a perceptive person, but his genius lies in absorbing himself in what he sees and piecing people’s last moments together through the eyes of a killer. This kind of perspective taking is rare in individuals on the autism spectrum, as Graham claims himself to be. Therefore, I would argue that absorption is the key trait allowing Graham to get inside killers’ heads; his inability to disengage from the disturbing images that run through his head confuses him and creates untoward consequences that demonstrate the perils as well as the promise of high levels of absorption.

Norman Bates is a more purely maladaptive face of high absorption. Absorption is also associated with dissociation, which refers either to the feeling that one’s self or surroundings aren’t real or to the experience of having done something without recalling having done it. As the seasons progress, Norman’s increasing absorption in his fantasies about his mother propel him from committing murders of women he desires to taking on his mother’s identity without recalling having done it in the morning. Norman’s emotions overwhelm him, and he uses his absorption to retreat into a mental world that’s safer for him, that’s anchored by his mother. It’s this fantasy component of openness and absorption that’s related to psychoticism, which represents a vulnerability to experiencing odd and unusual perceptual experiences consistent with schizotypal personality disorder and certain forms of schizophrenia. In essence, Norman Bates isn’t a psychopathic killer; he’s one of the rare serial murderers with psychotic experiences – in this case, that may be underpinned by absorption. Will Graham exhibits a form of dissociation that might superficially seem related to absorption as well, but instead (SPOILER ALERT) is more likely due to encephalitis than his personality.

Norman Bates is a more purely maladaptive face of high absorption. Absorption is also associated with dissociation, which refers either to the feeling that one’s self or surroundings aren’t real or to the experience of having done something without recalling having done it. As the seasons progress, Norman’s increasing absorption in his fantasies about his mother propel him from committing murders of women he desires to taking on his mother’s identity without recalling having done it in the morning. Norman’s emotions overwhelm him, and he uses his absorption to retreat into a mental world that’s safer for him, that’s anchored by his mother. It’s this fantasy component of openness and absorption that’s related to psychoticism, which represents a vulnerability to experiencing odd and unusual perceptual experiences consistent with schizotypal personality disorder and certain forms of schizophrenia. In essence, Norman Bates isn’t a psychopathic killer; he’s one of the rare serial murderers with psychotic experiences – in this case, that may be underpinned by absorption. Will Graham exhibits a form of dissociation that might superficially seem related to absorption as well, but instead (SPOILER ALERT) is more likely due to encephalitis than his personality.

Robin Williams and anhedonia

Warning: Ahead be spoilers for the little-seen movie The Angriest Man in Brooklyn and a frank discussion of suicide.

Robin Williams’ death hit me hard when it was first reported. I spent about a week watching his movies, comedy shows, television appearances, and even some old Mork and Mindy episodes to remember the depth and breadth of his talent. From the Captain of Dead Poets Society and the unorthodox therapist in Good Will Hunting to the madcap comic hijinks of Mrs. Doubtfire and Good Morning Vietnam to the sublimely creepy photo technician in One Hour Photo and malign Milgram clone in an episode of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, Williams’ acting talents were uniquely diverse.

His death’s lingering impact struck me when I watched The Angriest Man in Brooklyn tonight. It was the last movie of his released while he was still alive, and it features a scene in which his character jumps off the Brooklyn Bridge to attempt suicide. At that moment, the remainder of the movie didn’t matter to me. That scene was an eerie reminder of the nature of his death; his character’s survival of the attempt rendered even more poignant the death of his portrayer through similar means. Early attempts to explain his suicide focused on his history of depression and substance use, both of which are predictors of suicide.

Williams was reported to be suffering from the early stages of Parkinson’s disease at the time of his death (though later reports suggest he may have suffered from Lewy body dementia instead). Assuming that the Parkinson’s disease diagnosis was correct, Williams becomes one of the most striking exemplars of the anhedonia that frequently accompanies Parkinson’s disease. Specifically, because Parkinson’s disease entails reduced levels of dopamine, it’s reasonable to assume that the anhedonia in Parkinson’s disease relates to a decrease in “wanting”, the part of reward processing that’s involved in yearning for and approaching something that’s desirable. If very little seems truly desirable in your life, it’s difficult to make yourself get out of bed, do the potentially hard work in front of you, and keep going through obstacles that rise up.

One might assume that near the end of his life, Williams’s emotional life was the opposite that of his character in The Angriest Man in Brooklyn. Anger is an approach-related emotion, one that’s related to dopamine binding. Rather than being angry, Williams was described as depressed, anxious, and paranoid toward the end of his life. Clearly, finding good assessments of the anhedonia of Parkinson’s disease patients is critical, particularly to the degree it may share features with the anhedonia in other disorders like depression. If that’s the case, treatments for one form of anhedonia may be applied to other forms, saving the lives of thousands of people – including some of our most creative members of society.

Comments